After an unlikely meeting at the famous Bauhaus school in 1922, the artists Josef and Anni Albers, the most enduring couple to emerge from the Bauhaus movement, would describe the rest of their lives as a kind of two-person artistic powerhouse. Despite spending more than half a century together and enjoying flourishing individual careers, there were only three occasions on which the Albers collaborated artistically: Easter, New Year’s, and Christmas.

Nicholas Fox Weber, executive director of the nonprofit Joseph and Annie Albers Foundation, who wrote a 2020 visual biography of the couple, a close personal friend of the couple, says the Albers “had great respect for each other’s work.” Annie and Josef Albers: Equal and Unequal. But the couple, who got married in 1925, were content to stay firmly in their fields. “He was a weaver and she was an artist, and neither was going to enter the other’s realm,” explains Weber.

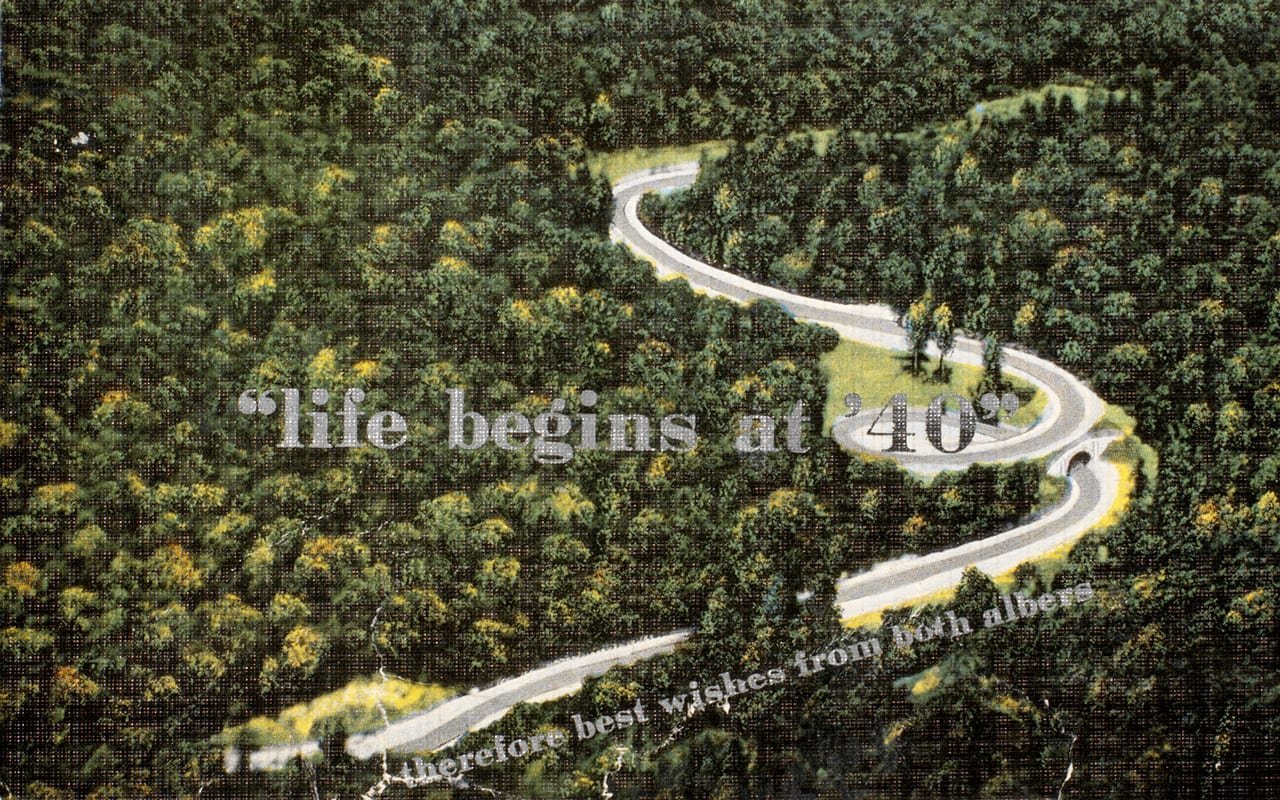

However, they will deviate from this rule for three select holidays where they work together to create commemorative art. True to their innovative perspective, the Albers’ holiday cards are more than simple greetings, but instead embrace design-driven holiday traditions. They also offer a rare insight into how two of the most influential designers of recent times spent Christmas as a couple.

THE BAUHAUS APPROACH TO GREETING CARDS

The foundation’s collection of Albers’ holiday cards begins in 1934, the beginning of a new chapter in the couple’s life. A year earlier, the Bauhaus was forced to close by political pressure from the Nazi party—pressure that prompted the Albers to move to the United States. Both Joseph and Annie taught at Black Mountain College in North Carolina. from future Christmas cards.

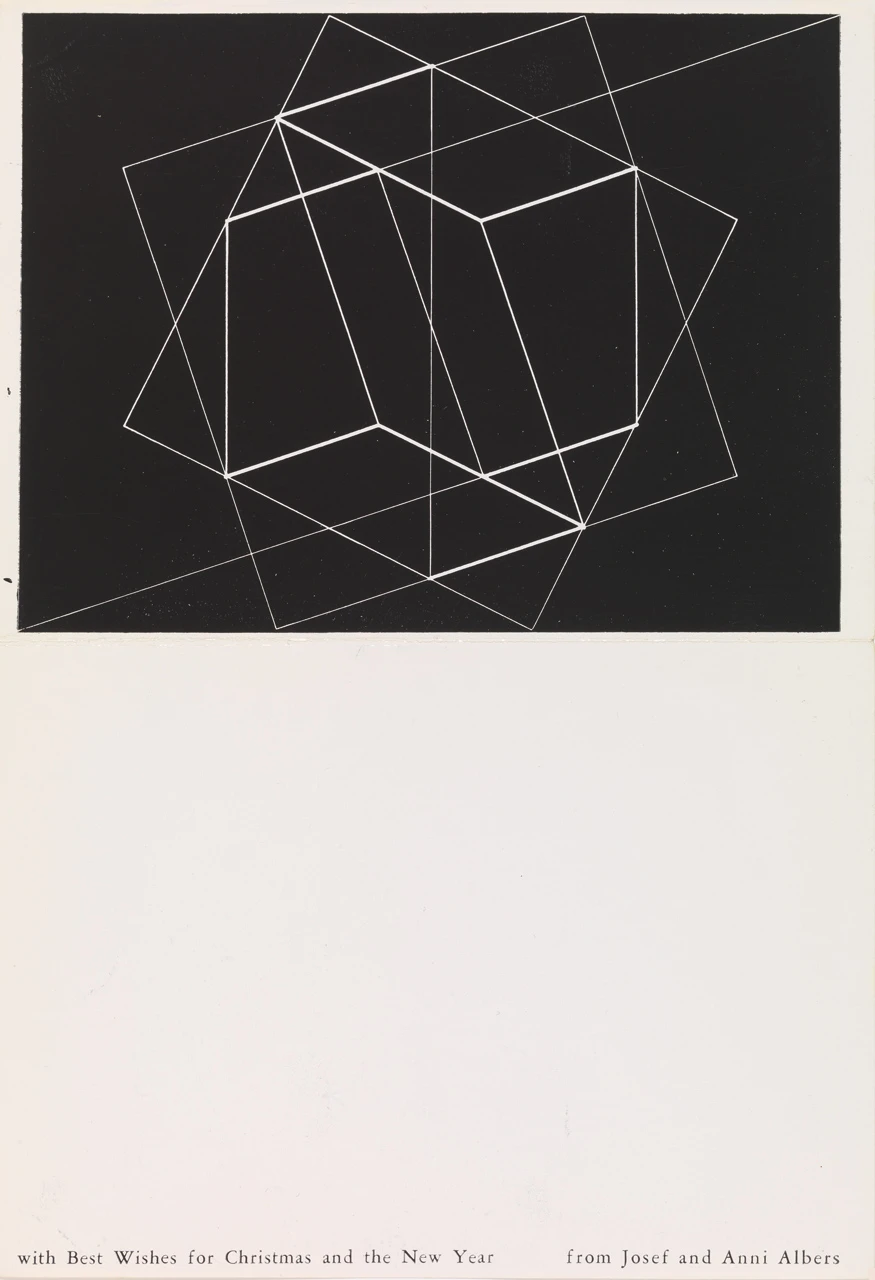

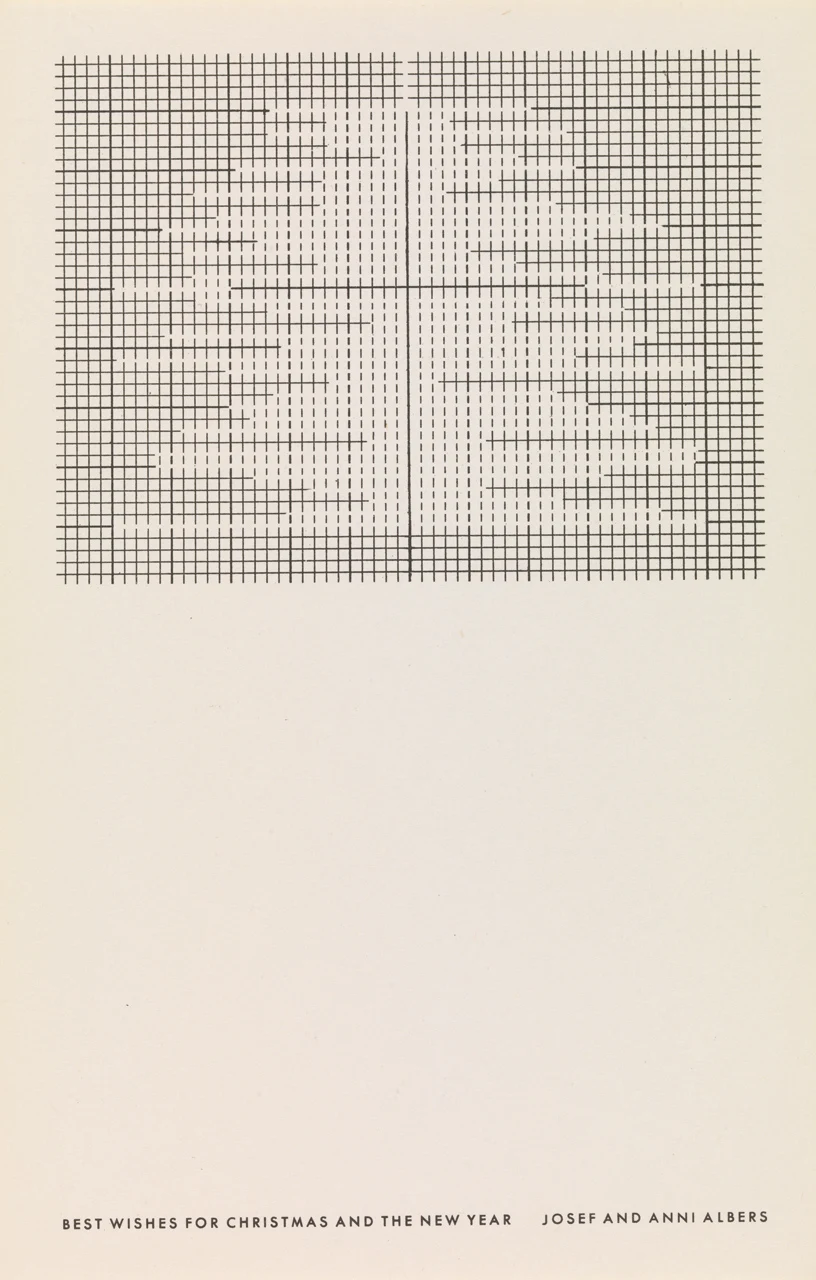

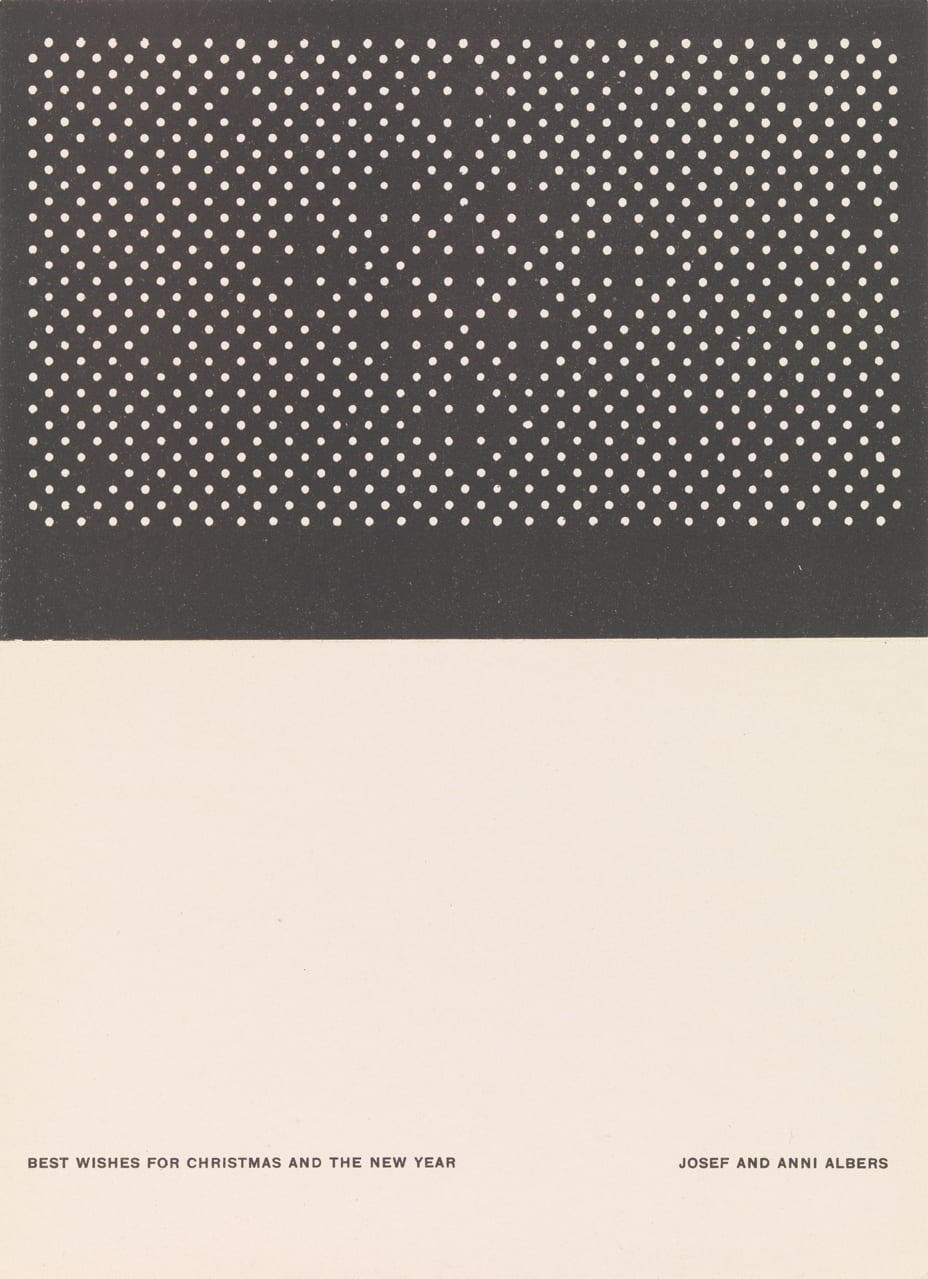

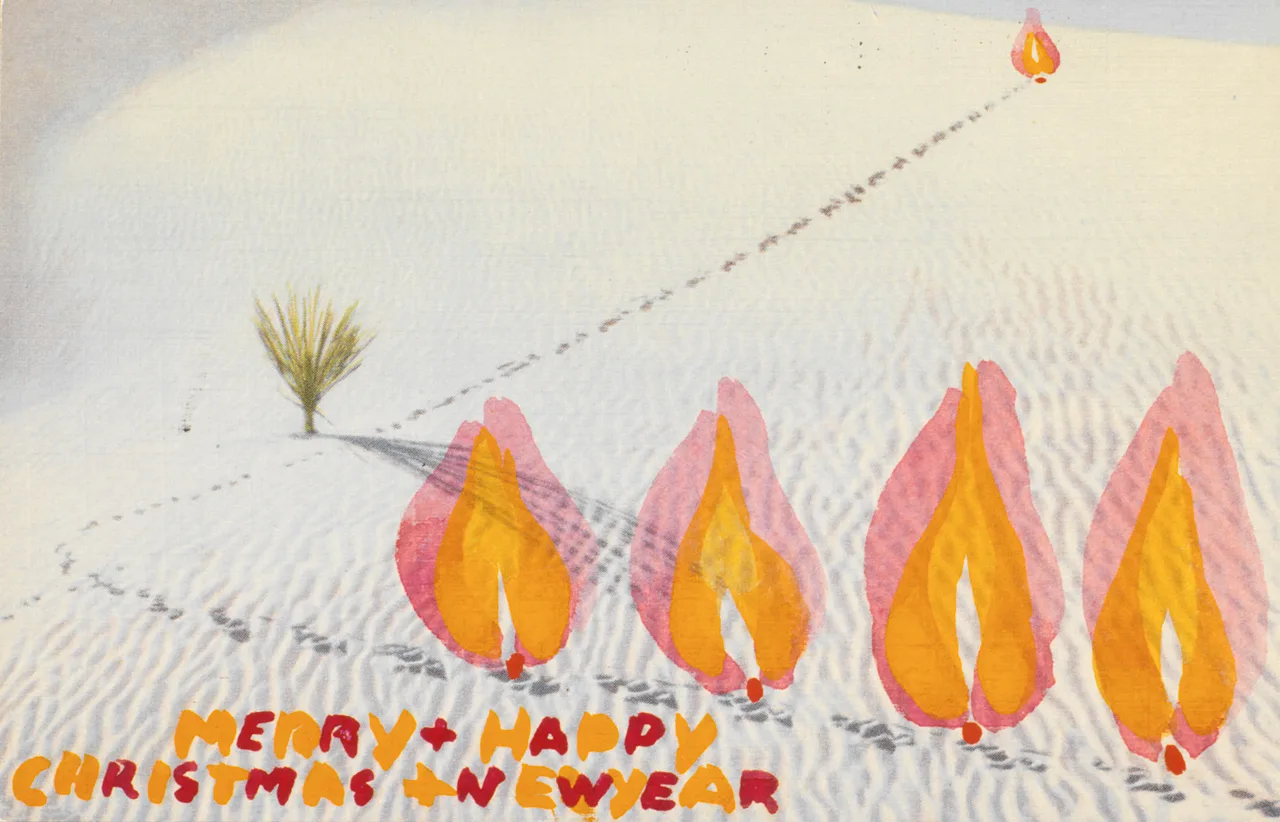

At first glance, the cards don’t look exactly like traditional Christmas notes (except for the usual “Merry Christmas and Happy New Year, Josef and Anni Albers”). Rather, each is its own exploration in graphic design, featuring details such as textile-inspired dot patterns, abstract letterforms, and hand-altered postcards.

The couple’s 1934 Christmas card was one of the first cards Joseph printed at Black Mountain College. Its simple, all-red typeface reflects a distinctly Bauhaus emphasis on simplicity and legibility over ornamentation, while the composition as a whole embraces the design ideal of balanced asymmetry. Weber once said Dezeen About Josef and Anni’s shared design philosophy, “They were both very interested in form following function. It was all about understanding the process and the materials and the technology to put them together.

In later years, particularly the 1950s and 1960s, the cards show an increasing flair for form and line, using a minimalist black and white palette as a starting point. In 1951, a partially erased grid suggests the outline of a Christmas tree. The following year, the pattern, created only from white dots, evokes a kind of holiday textile, reminiscent of some of Annie’s groundbreaking work in the field of textiles.

A Christmas tradition

A closer look at the cards reveals some clues about how the Albers spent their Christmases, Weber says.

“There were a lot of things they didn’t do, but they celebrated Christmas in a simple way for themselves,” he says. “I say their simple ways because they spent time together at home – not socializing – and listening to Bach. Goldberg Variations. When you look at holiday cards, you can really imagine the clarity of practicality Goldberg Variations: lightness, a certain rhythm.”

Aside from the basic art featured on each card, the Albers also paid a lot of attention to the actual construction of each mission. Weber says the letters were so well-crafted that many of the Albers’ friends framed them every year.

“Holiday cards are very closely related to Albers’ beautiful stationery. We are talking about the days when most things were done by letter. Annie and Josef had particularly beautiful blanks – you could tell that great attention was paid to every detail of the distance. The cards follow the tradition of blanks. The holiday itself was important to both; They both had a sense of Christmas tradition,” says Weber.

First, Annie came from a wealthy family, once sharing distinct memories with Weber of a carriage ride to her uncles’ house, where she and her brothers and sisters ate delicacies such as beluga caviar, rock crab and ice cream. cream cake. Growing up in a middle-class family, Josef enjoyed these extravagant tales. In 1975, Weber personally purchased the ingredients for Annie and Josef to enjoy a Christmas dinner reminiscent of those lavish early years. That holiday season was the last the two shared, as Joseph died the following March.

“To this day, at Christmas time, I long for the pure delights of Albers’ last Christmas together and have to eat such an atavistic meal,” Weber wrote in an essay on the subject. Air mail last year. “And I listen to Glenn Gould playing that phenomenal Bach music, I know that Josef Bach made beautiful stained glass windows in Leipzig very close to the church where he was longtime organist, and I know that Bach’s high intelligence suited the Albers. perfect.”